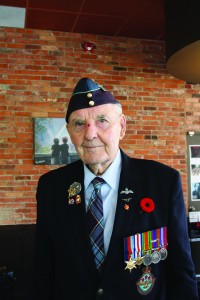

As we all wear our red poppies over our hearts, we are remembering the many lives that have been lost in the Armed Forces’ line of duty. The survivors are also recognized for their courage and efforts in fighting. One such survivor is Royal Canadian Air Force Pilot, Lloyd Bentley of Brantford, who took part in the fight against the German Nazi army in World War II.

Bentley jumps in to tell his experience of serving in the air force like it just happened yesterday. He admits, “People tell me I talk a lot,” with a wide grin.

Becoming a pilot was not a dream of Bentley’s, but the idea of being in the army and having to shoot people was a definite nightmare. The Air Force was the sensible way for Bentley to contribute without going against his morals.

Bentley took just about every Air Force course there was out there, including Initial Training School in Toronto, Ontario; Elementary Flying School in Windsor, Ontario; Service Training School here in Brantford, Ontario; Navigation School in Summerside, Prince Edward Island; Advanced Flying School in England and operational training with torpedo bombs in Northern Ireland. The joking words from one of his instructors at Brantford stuck out to him, “Well Bentley, there’s one consolation: not always the best pilots live the longest.” Bentley chuckles as he recalls the remark.

Bentley speaks from experience when he says, “Hitler would have been the biggest bully in history.” Bentley was bullied throughout his childhood as he was much skinnier than most of the other boys his age, but that never stopped him. His chest rises as he proudly says, “I was sissy Bentley and I didn’t give a damn!”

On June 5, 1944, Bentley and his compatriots and allies received a letter from Dwight Eisenhower, the President of the United States at the time, and General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces. The letter outlined the command of, “The destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world.” It was referred to as “D-Day”, or “Operation Overlord”, and was rescheduled to the following daydue to weather conditions. The mission was to invade Germany’s hold on Normandy through five designated beaches: Sword Beach, Juno Beach, Gold Beach, Omaha Beach and Utah Beach.

Bentley’s air force division was commanded to Sword Beach alongside the British Infantry division, where Bentley flew a DC-3 Dakota. He remembers looking down on the thousands of ships and explains his impression that, “They looked like they were so thick, that if you had long legs, you could probably walk back to England on the ships.”

Within a week of “D-Day”, Bentley was flying back from the beaches, wounded. Once the wounded were taken to the Air Evacuation Center in England, the medics had to sort through the soldiers with different injuries to decide which hospital they were to be sent to. “It was quite a grim thing to see,” Bentley says as he shakes his head side to side.

Bentley was also a part of the unexpected failure of “Operation Market Garden” on September 17, 1944. The plan was to force airborne entry into the Northern end of the “Siegfried line”, the line of German defences, within the Netherlands by means of paratroopers and gliders. Only a small margin succeeded to capture bridges between the Eindhoven and Nijmegen rivers.

Bentley did not fly until the following day, and landed within Ginkel Heath. Bentley’s job was to drop supplies and paratroopers to the beaches all that week. However, that Thursday’s flight was a difficult one. When they started back to England to gather supplies, Bentley began to see unfamiliar lights. He explains that he had a fortunate position behind a small cloud, and says that “within a minute I could see flashes all out of my little cloud.” The wing of a German Fw-190 flashed before his eyes as he realized they were under attack. Half of their transport was shot down, and Bentley was a part of the six out of 13 aircrafts from his squad that made it back to England.

That Saturday was another struggling flight, as Bentley’s troops were again in air to drop supplies back to Ginkel Heath when the Germans managed to shoot out their oil lines. They only made the trip back as far as Eindhoven, where luckily their British allies had taken control of an airport where they could make an emergency landing. “That night I slept on the floor under about a 20 foot painting of Hitler, it sure gave me a weird feeling,” Bentley recalls with shivers.

Bentley feels sorry for the German soldiers as he explains that, “They were brain washed. They were apparently the hardest people our soldiers had to fight, because today we would have probably called them terrorists. They were willing to die for Hitler.”

Since the war, Bentley has visited the Netherlands many times to pay tribute to those who have fallen. While visiting the cemeteries that held the members of his allies, he is saddened to realize that about 75 per cent of the deaths had ranged from the ages of 19 to 21. “But the saddest I felt – because I ended up having some really good German friends – was in the German cemetery,” Bentley says with a mourning look on his face. About 90 per cent of the German’s deaths had ranged from ages 17 to 19.

These are but a few pieces of Bentley’s experiences during his two years of training and two years overseas in the Armed Forces’ line of duty. He has attended many schools to talk of these experiences since the war. The piece of advice he stresses the most for the students is to, “do the best for yourself and never mind what other people think of you.”