“You never know when you answer the phone if someone is going to die. If you don’t pick it up quick enough, are they going to kill themselves?”

Debbie Matthews, 55, struggled sporadically throughout her 33-year career as a 911 dispatcher for the Waterloo Regional Police Service.

Matthews has coached a five-year-old on how to help his mother survive her stroke, listened to suicidal people shoot themselves, and had to do a hostage negotiation to get 18 people out of a building alive.

Matthews recalls one night when she had a suicide call, then listened to a man whose throat was slit “gurgle out” while in his brother’s arms, and due to her resourcefulness on the phone, the culprits were arrested exactly 90 seconds later. Then, she had another suicide call.

When she walked out to her husband that night after her shift, she was unable to even get into the car.

“’I can’t,’ I said to him. ‘I can’t breathe.’”

Addictions Counsellor Fiona Apperson said, “When you hear a lot of trauma, it can really affect you and you can be triggered in many ways so I really have to detach myself [when I come home].”

Apperson, 54, is an early intervention counsellor at Bridges to Health, a House of Friendship program. She runs workshops to improve the spiritual, emotional and physical health of women with addictions.

Each day, Apperson hears the patients open up about their “raw feelings”, pain and trauma which triggered the substance abuse.

“It can be very draining. Especially when somebody comes back and says ‘Okay, well now I have lost my job or my children have been apprehended,’” she said.

Apperson adds that she has lost patients due to overdoses which is extremely difficult to deal with.

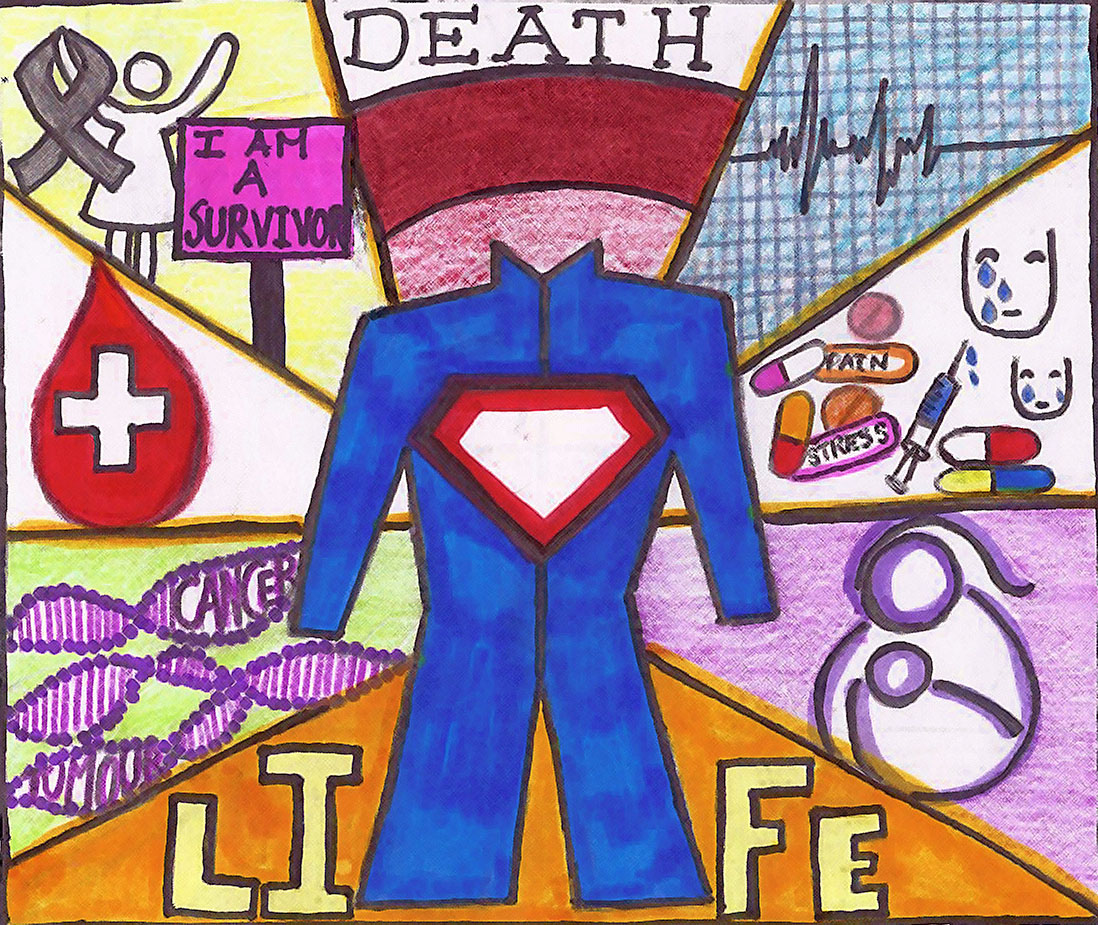

Sue Miller, a certified oncology nurse at the Grand River Regional Cancer Centre, spends each day talking and working with people with a disease many know all too well. Miller obtains a full medical history and performs a standardized test on patients that assess their emotional wellbeing. This allows the team to decide on how they can improve or change their experience the next day or for the near future.

Miller says that during follow-ups and consults, patients often discuss how their cancer has affected their family, relationships or career: “A lot of them are very quick to share what is going on.”

“It’s surprising … how much emotional content is brought to the visit, in terms of their personal stuff, that doesn’t really have anything to do with the visit, but it does because it’s their life,” Miller said.

Miller says that there are a few times a year when she “hits her breaking point and just [has to have] a good cry.”

Just last week, a doctor and Miller had to tell a patient she has been working with for years, who she describes as “an extraordinary person you sometimes come across in life”, that he or she only had a few more months to live.

“I was fine in the room. I was a good support in the room. But as soon as I left and went back to clinic, I just completely had a breakdown.”

For 911 Dispatcher Matthews, a particular type of call gets to her.

“When a child calls me and is hiding in their closet and says to me ‘I know I’m going to get grounded because I’m not supposed to call the police but daddy is really hurting mommy this time.’ … I hang up from those calls and I cry.”

“If I wept over every person that died, I wouldn’t be able to give help to the next person,” Matthews said. “There’s a lot of darkness but you can’t let it eat you up.”

Matthews says these types of jobs can affect your personal relationships.

“You are always investing yourself in other people’s troubles, sometimes there is little energy left to deal with your own or those around you,” she said. “And you feel isolated … most has to remain confidential so you can’t vent or share your day with your loved ones.”

Instead of having negative feelings when she learns of the patients’ relapses, Apperson is able to avoid taking things personally and instead focuses on moving forward.

“I’m not shocked or anything, I just keep assuring them that at least they came back … I say ‘Okay, let’s talk about this. What happened?’”

Although Matthews, Miller and Apperson deal with emotionally challenging situations, they all describe their jobs as rewarding and invigorating.

Apperson witnesses a huge transformation in her patients after just two weeks of education, hope and direction.

Miller said, “Despite the difficulties that we face each day, in terms of what people are going through, for the most part, I leave each day feeling like I have helped somebody.”